Children are not their emotions, so why are we encouraging them to be?

How children can learn to separate feelings from actions

“Man is disturbed not by things, but by the views he takes of them.”

— Epictetus

History’s most enduring cultures often share a common core principle: we are not our thoughts and, therefore, we are not our feelings. Yet, modern day parenting approaches seem to be centred around an obsession with the emotional state of children. This push to validate every emotion comes from a place of compassion, but it’s impossible to read a child's mind, so we end up guessing what they are feeling, and unintentionally reinforcing their behavioural choices instead.

A friend of mine once punched a hole in a wall after conceding a goal whilst playing the video game FIFA. Were his feelings valid? Maybe, but were his actions? No. We looked at him like he was insane, covered the hole with a poster, played on and still tease him about it 15 years later.

Why are children so emotional?

Theory of Mind: The ability to understand that other people have thoughts, beliefs, desires, intentions, and perspectives that are different from one's own.

It's not that children's feelings aren't important. Of course they are. But, their prehistoric, untrained instincts are often improperly applied to our modern context, causing exaggerated emotional reactions. Furthermore, children are little narcissists by default until they develop theory of mind around the age of four or five - but their feelings are in full swing long before those skills are embedded. It’s nothing personal, they just live in their own world, and you’re messing with it.

“Feelings are real, but they are not always right.” — Marc Brackett

A two-year-old might understand when you explain that play time is finished because we need to go to the shop in order to get supplies, feed the family and survive the winter. However, it’s more likely all they see is “my play has been ruined by the evil fun police”, hence the emotional outburst. It’s no coincidence that children who take longer to develop a theory of mind, a characteristic common in ADHD and autism, struggle with their emotional regulation and tend to have more behavioural challenges.

The science: feeling vs thinking

The amygdala: processes emotions like fear, anxiety and aggression, detects threats and helps store emotional memories.

The prefrontal cortex: is crucial for executive functions like emotional regulation, impulse control, problem-solving and understanding others perspectives.

Amygdalae are much more reactive in children, which makes evolutionary sense due to their vulnerability in the world. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) responsible for assessing whether a threat is actually viable or not takes time to mature enough so that it can essentially take control. Interestingly, it has been suggested that the PFC strengthens and becomes more efficient with repeated use, especially when children are supported in using strategies that promote emotional regulation through cognitive behaviour techniques. This means children don’t need to wait around for the PFC to become more active on its own, especially when it comes to those who are struggling.

What can we do?

“You have power over your mind—not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.” — Marcus Aurelius

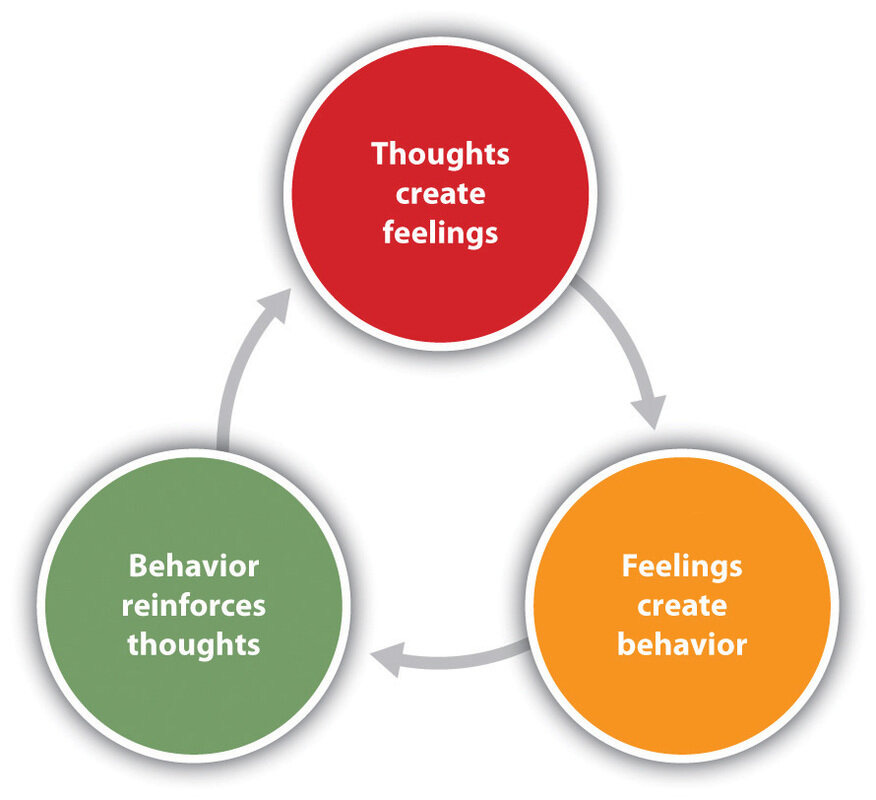

Children need to train their control tower so that it’s effective in difficult situations. This is done by identifying thoughts, analysing subsequent feelings and employing strategies to reappraise the current scenario. We can support them to achieve this by:

Analysing thoughts and emotions and reflecting on actions.

Identify the negative thoughts. Was the situation as bad as it seemed at the time?

Was the reaction fair or was it an error? Align thoughts with evidence.

Determine the problem and a plan to solve it better next time.

Examine how they could use that plan to adapt their thinking in future.

Discussing basic strategies that they can implement to regulate emotions.

Square breathing, basic meditation, having a calm space, listening to music, using a fan to physically cool down.

Identify the negative thoughts and analyse them in real-time (this takes practice).

Using physiological language to explain why these strategies work.

When we’re angry, our heart rate increases, our body temperature rises and we get sweaty. Becoming more aware of their body helps to identify when it's time to deploy a strategy.

Incentivising the use of these new techniques through external rewards, praise, sticker charts etc. Eventually, they will start to experience the natural social rewards of regulating their emotions.

When they regulate their emotions, no matter how long it takes, it needs to be rewarded.

Having lines you do not cross, i.e. hitting. Consequences must make the old way to communicate their emotions less appealing in order to dissuade them from using it. Remember, we are modifying the actions, not their thoughts and feelings.

Using visuals to help identify what emotion they are feeling, what that looks/feels like and how to get back to baseline.

Regularly discussing what thoughts and emotions are and why it's important to analyse them.

The brain's best physical and mental response to a stimulus.

Social consequences for behaviour, positive and negative, now and when they grow up.

More serious consequences as they grow up if they don't learn to control their actions.