“I'll give you something to cry about”: Enhancing emotional resilience in children.

Should we always validate feelings?

Help shape The Misfit Memo's new programme.

Hey everyone,

I’m thinking of putting together a programme to help parents cut daily battles with their kids in half—so they can get rid of power struggles, stop feeling overwhelmed and start enjoying parenting again.

It would be a simple coaching system that shouldn’t take longer than a few minutes a day.

If you or someone you know would benefit from this, send a message below, and I’ll get back to you with more details! Thanks for your help.

"A good place to start is by assuming that your emotional reactions are not always reliable guides to reality."

- Jonathan Haidt, The Coddling of the American Mind

What's changed?

We know that a childhood of emotional neglect and rejection can manifest itself in many negative ways such as low self-worth, shame, hostility, social withdrawal etc. However, social fallouts caused by behavioural skills deficits are also extremely detrimental, and validating Jimmy’s decision to throw hands at the kid who took his toy, is far from ideal.

Modern approaches to parenting focus so heavily on the emotional state of the child that it has caused parents to panic and rush to fix every meltdown as quickly as possible. What is also prevalent is the habit of pre-empting petulance where adults panic over the mere thought of a conflict, especially in public, causing them to give in to demands before anything’s even happened.

Should we always validate feelings?

"The greatest remedy for anger is delay." – Seneca

If the aim of raising children is so they can participate effectively in the world, then why has it become so mainstream to validate volatility? Children don’t instinctively know how to behave in society, but they are incredibly adaptive and learn to survive by observing how adults respond in certain situations. In the same way that children may learn to shut down if their worries are met with hostility and rejection, they also log acceptance of massive overreactions as an endorsement of that behaviour for similar, future scenarios.

What we end up doing, by worrying so much about their current emotional state, is validating actions caused by their emotions, and subsequently reinforcing less than ideal communication strategies. All this suggests to kids is that their emotions are the most effective way of communicating their needs, rather than coherent communication, which is not a long-term solution.

Conflicts and meltdowns are inevitable, but instead of worrying about them, use them to see where your child lacks certain skills, rather than give in and kick the can down the road. It’s not fair to protect kids from their faults, instead we should be pushing their boundaries to see where they require new skills.

What can we do?

A child’s emotions are like a storm—strong but fleeting. The wise parent does not fight the storm but teaches the child how to sail through it. - Stoic principle

View children from the perspective of a year or two in the future. Yes, tantrums are commonplace during the terrible twos, but by ages three or four they are a real nuisance. To avoid a prolonged tantrum period, start analysing the reasons behind your child’s behaviour ASAP, so you can reinforce more useful ways to communicate early on. This is especially important for those with attention difficulties because they are less likely to pick up these skills through social observation.

Here’s how to develop emotional resilience:

Consequences: children should understand that it’s not their emotions that lead to consequences, but their actions.

Reward/praise when children use strategies to get themselves under control;

Reward/praise socially appropriate behaviours (don’t take them for granted) like politeness, putting effort into something or overcoming adversity;

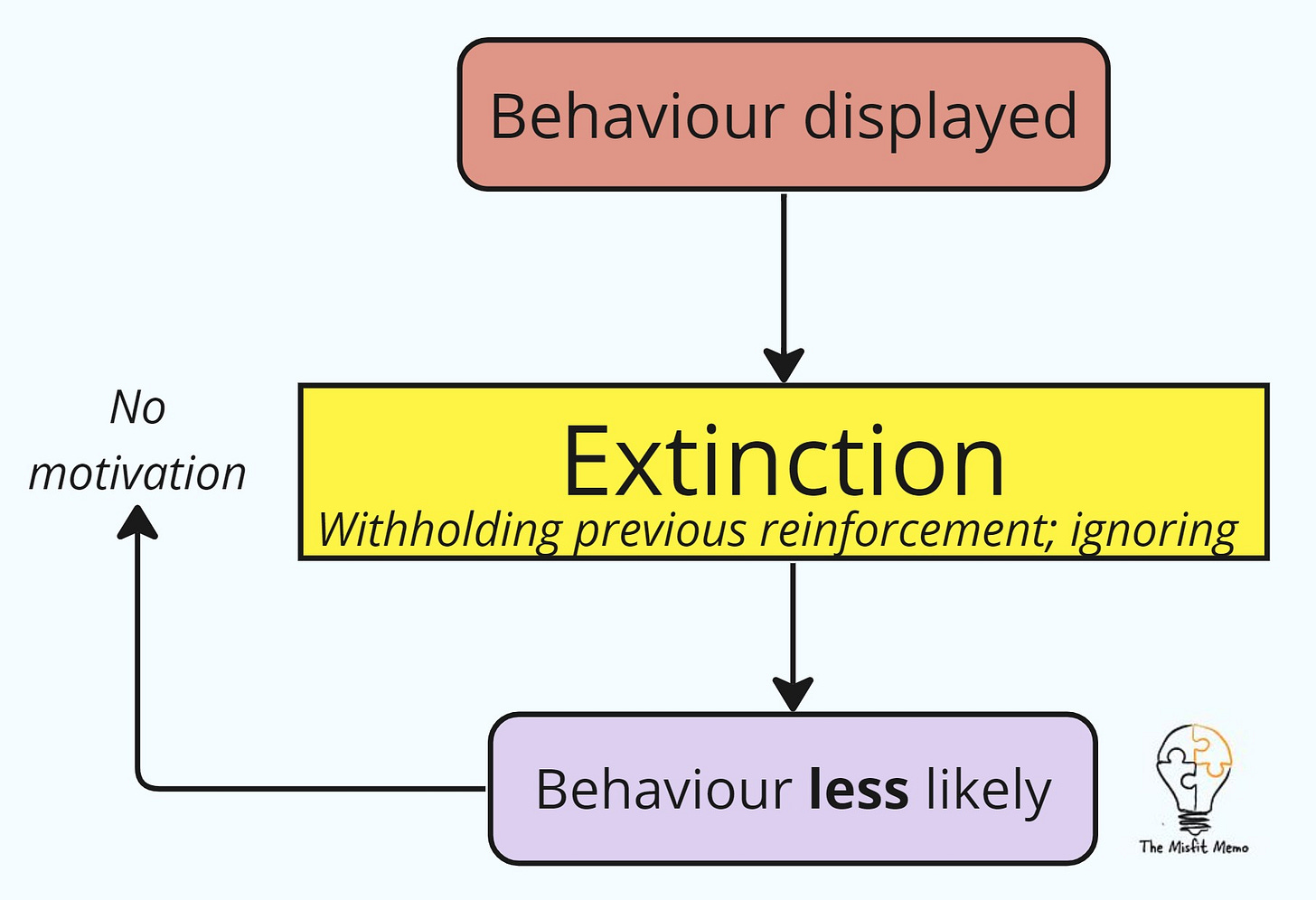

Ignore big reactions if it isn't a big deal and everyone is safe;

Remind them that you’ll converse when they are calm and use appropriate language. (FYI it’s OK if they’re not ready to talk about it in the moment).

Focus on the controllable: children cannot control what others do, so we must focus on our reactions to events.

Point out the differences in our personalities that may lead to disputes and fall out. Some like rules, some bend them. Some like to wind people up, some don’t.

Encourage children to be in control of their reactions to others. Others can’t make you mad, but you can choose whether to be mad at what they did.

Strategies: Explicitly teach children what to do in case of an “emotional emergency.”

Breathe: square or 4-7-8 breathing techniques, for example, signal your body to relax, lower your heart rate and blood pressure, reduce cortisol and focus brains on something other than their annoyance.

Calm space: praise them for taking themselves off to a known calm area, when available, where they can decompress. Have toys and play things here to distract their mind.

Physical exercise: walks, either together or shadowing if they need space, work wonders.

Sensory videos on YouTube: Avoid devices if possible, but videos like this are hard to beat.

One of my favourite expressions from my childhood :)

This is an interesting take, and I agree that emotional resilience is a crucial skill for kids to develop. Teaching children how to regulate their emotions rather than being overwhelmed by them is essential. However, from an attachment perspective, we have to be careful not to confuse validating emotions with endorsing behaviour. The two aren’t the same.

Circle of Security which I teach talks about when children express big emotions, it’s a signal that they need help organising their feelings. If we ignore their reactions too often, they may not learn how to regulate them but instead suppress or escalate them to get a response. Rather than dismissing emotions, the goal should be to help children make sense of what they feel, while also guiding them towards more constructive ways to express it.

For example, if a child hits another child in frustration, we can acknowledge their anger (I see you’re really upset) while setting a boundary (I won’t let you hit) and guiding them toward a better response (Let's take a deep breath and talk about what happened). That way, we’re not reinforcing poor communication, but we are also not shutting down their emotions. Both matter for long-term resilience.

It’s a balance—kids need to feel safe in expressing emotions, but they also need to learn that emotions don’t justify all actions. The key is helping them feel understood first, then teaching them skills to navigate life more effectively. Thoughts?