What really frightens and dismays us is not external events themselves, but the way in which we think about them. It is not things that disturb us, but our interpretation of their significance. - Epictetus

There are many misconceptions about anxiety and stress, which I admittedly held up until recently. As anxiety levels continue to rise in children around the world, we need to appreciate the biological mechanism behind it, whilst understanding the debilitating effect it can have if allowed to overwhelm us.

Anxiety vs stress

Anxiety and stress are often used interchangeably, and although they overlap, they require different approaches. Stress is, usually, a short-term response which sends a chain of signals from the brain to respond to a specific - psychological or physiological - stressor. Anxiety, on the other hand, is in response to generalised and ongoing worries about one or multiple aspects of your life. If used correctly, they both tell us that we have a problem that requires action to solve, but allowing the feeling to overwhelm us can be debilitating. This is why, instead of protecting children from anything that will cause stress or anxiety, we need to give them the tools and strategies to cope with and use this natural instinct to their advantage. It’s no coincidence that, as anxiety in children rises, so have levels of overprotective helicopter parenting (and teaching). By understanding the mechanisms, we can raise more resilient children.

Why we worry

Even though humans have been evolving over the last 4 million years, most of our biological systems, like dopamine, have stayed the same. Anxiety, from an evolutionary point of view, is designed to keep us alive in the following ways:

Threat detection - more effective at identifying potential predators and analysing hostile environments

Risk assessment and planning - being proactive and planning for potentially negative events

Social cooperation - avoiding social conflicts in tribes and having the mutual protection of a community

Avoidance of threatening situations - unpleasant experiences leave lasting impressions so that we recognise and avoid making the same mistake again

The issue is that this system doesn’t care if it’s a mammoth or a maths test, it responds in context to your life experience and genetics.

Nature or nurture?

Both genes and our environment have a significant impact on how we perceive the world, hence why the old debate has been redefined as ‘nature via nurture’ instead. Our susceptibility to anxiety is heavily correlated with neuroticism, which is the personality trait disposition that predicts - consistently - how prone we are to negative emotion, i.e. the lens through which we view frustrating, stressful or threatening situations and therefore, how we choose to react. People high in neuroticism have a tendency to: take things personally; try to predict the future and apply intentions to someone’s actions. Therefore, different levels of neuroticism cause people to perceive the same scenario in distinct ways, explaining the discrepancy in the anxiety experienced when organising a holiday or hosting in-laws. Evolutionarily, it makes sense to have a mixture of neuroticism in a community, due to it being equally detrimental if no one cared about the threat of tigers as it would to have everyone being in a constant panic about rustling bushes.

Why is anxiety rising in children?

There is an increasing body of research suggesting that our recent approach to anxiety in children is another example of how mental health strategies have drifted away from logic and science towards a feelings-based attitude. One that sees freaking out if a child goes through anything remotely difficult, as useful.

These days, there is an (albeit natural) tendency, for parents to shelter their children from feelings of negative emotion, which is detrimental to their development, as they may never learn to manage those feelings effectively and instead, attach negative associations to them. It is, therefore, more effective to teach children that the feeling of anxiety is just a form of thought that helps us work through various scenarios and that it is not the events themselves causing these emotions, but our interpretation of their significance. In his book, The worry cure, Robert Leahy demonstrates how 85% of things people worry about turn out better than they predicted (or didn’t even happen) and 80% of the time we deal with it more effectively than we thought we would anyway.

Strategies to combat anxiety

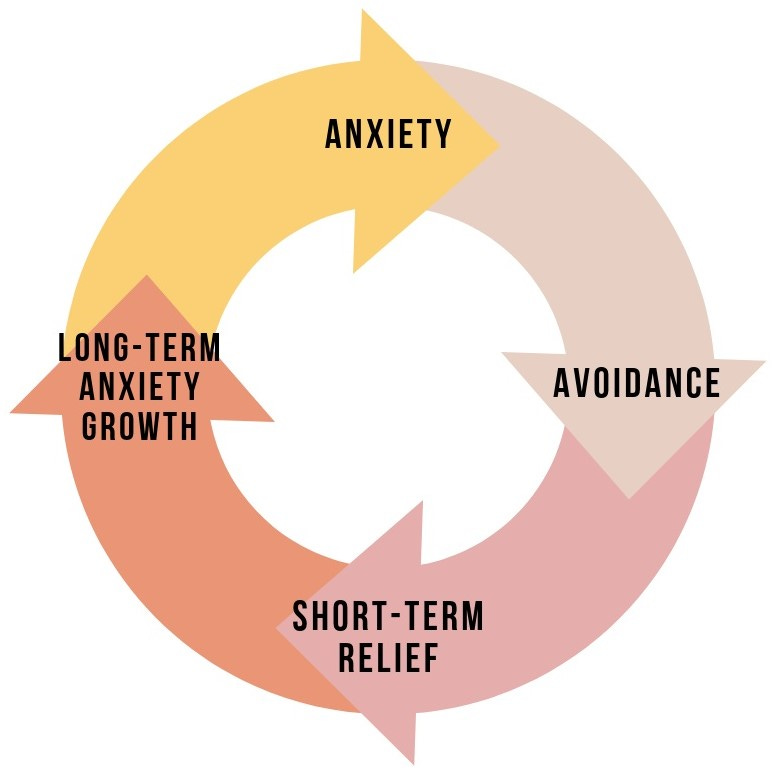

The number one way people try and cope with anxiety is avoidance, but a problem delayed is a problem magnified. It is beneficial to understand that children don’t need to get rid of anxiety, but instead, develop bravery in the face of challenging situations. Bravery is just action in spite of fear, you cannot fake it.

Here are some strategies for anxious children:

Take on challenges voluntarily, rather than avoid them

Break challenges up into small steps - easiest to achieve first and work from there

Do uncomfortable things often - become comfortable with uncertainty, mixed feelings and limitations

Don’t fear failure, but instead, see it as an opportunity to learn and develop

Memories that make us anxious long after an event are fears of unsolved failures

Our brain will continue to identify it as a potential danger until it’s dealt with

Avoidance signals running from a danger you cannot face

Bring it to mind voluntarily and plan for a similar circumstance

Exercise

Consistent exercise is the most effective strategy for any mental health concerns - including therapy, counselling and medication

Write down scenarios that worry you and set aside time to deal with them

Most of them will not be as concerning by then

Emotions are temporary and don’t always need to be acted on

Any that are still valid - write a plan for

Anxiety is sometimes just a lack of preparedness

Think about what makes you anxious over and over until it starts to feel mundane

Bore your brain of the issue

Think about previous scenarios that made you anxious, were they as bad as you thought, and did you deal with them better than you thought you would?

Is it a productive or unproductive worry?

If you can’t do anything about it, get rid of it

If it is worth worrying about, come up with a strategy

Think about the advice you would give a friend in your situation

We are much better at helping friends than ourselves

If you go through a catastrophic failure, write out all the ways it will affect your life

What parts of your life will continue as normal

In summary, anxiety in children is getting worse, which can have severe long-term health consequences. As the world gets safer, children are exposed to fewer dangers (a good thing) which means that we must manufacture resilience by teaching children how to deal with stressful events. What doesn’t help is adults overreacting in situations, either in their own lives or their child’s. Children learn how to act in society by observing us and mimicking our behaviour, so if adults can’t regulate their emotions, how can we expect children to? Children have the capacity to be braver and more capable than we think, and developing these skills early significantly enhances their future prospects.